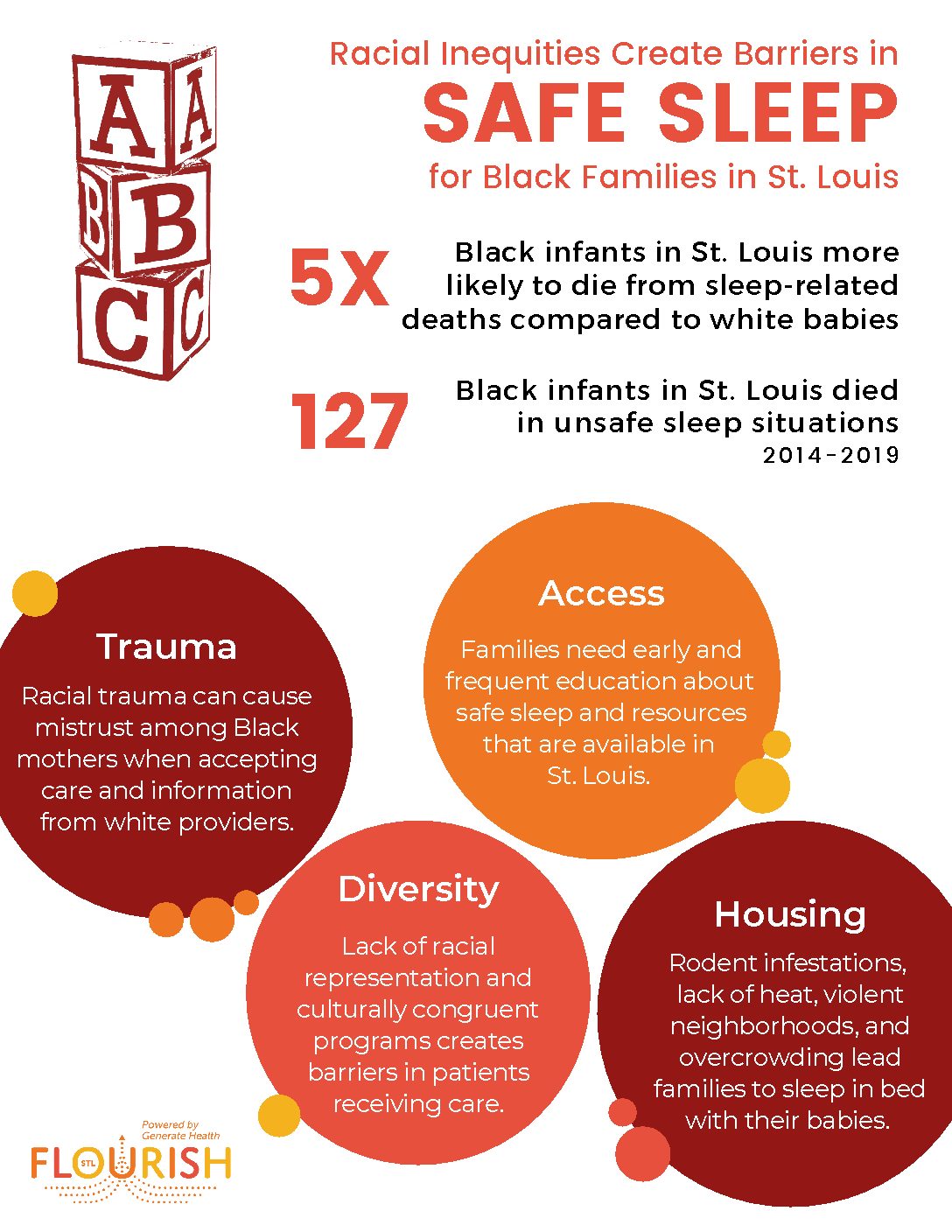

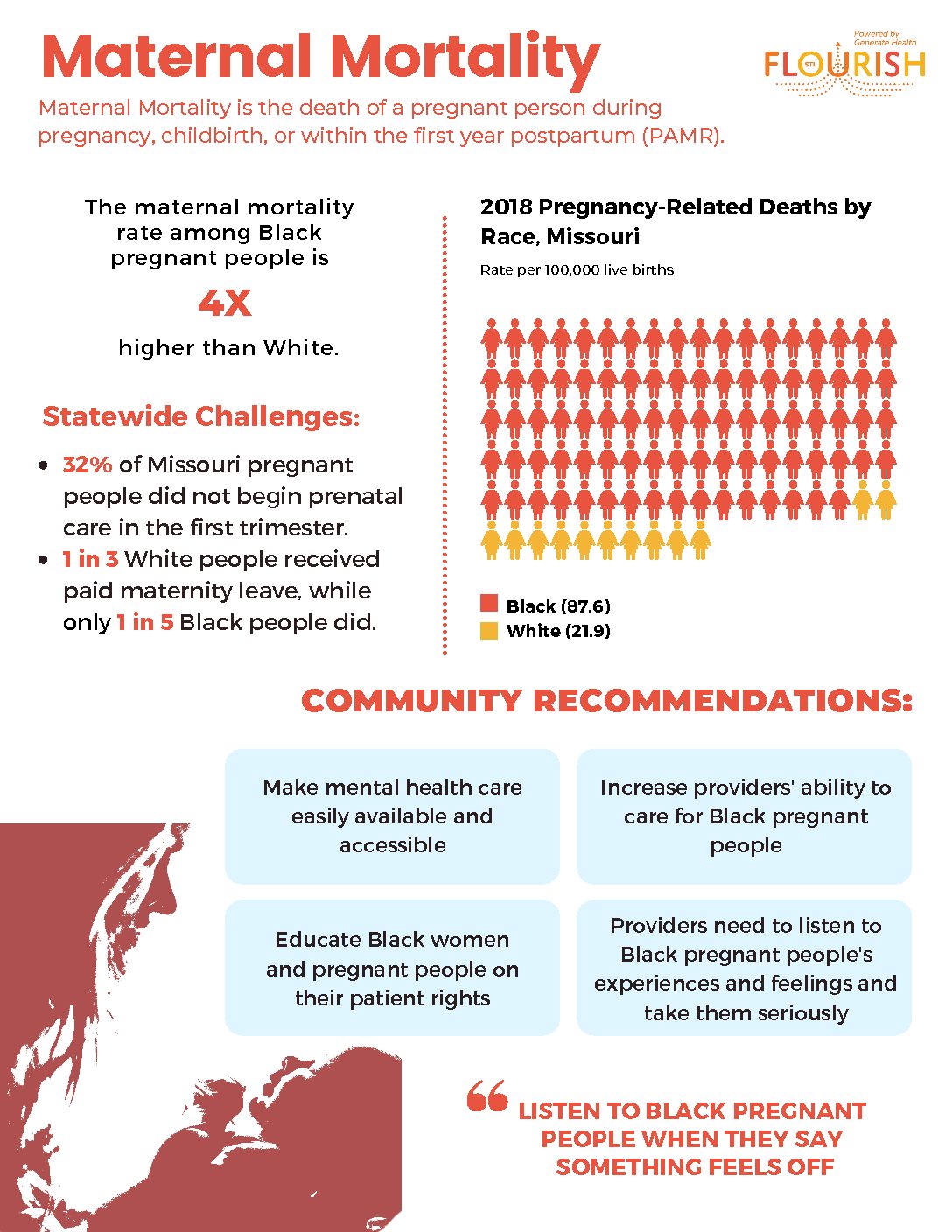

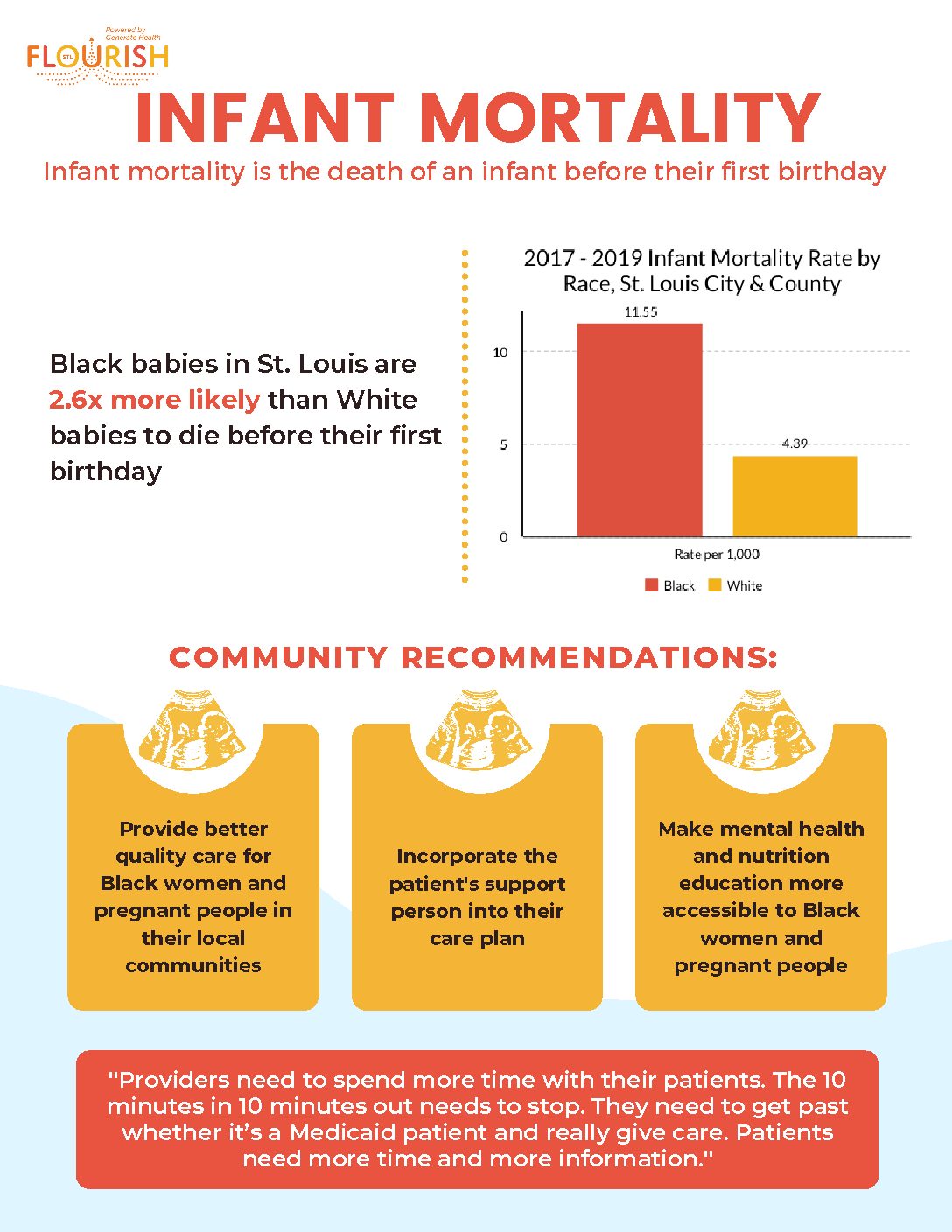

Black babies in St. Louis are three times more likely to die than White babies, and will continue to be at risk until we achieve racial equity, a state in which race no longer predicts outcomes. That’s why FLOURISH established a goal of zero racial disparities in infant mortality by 2033.

“Our cabinet came to this decision after months of conversation and research,” said Kendra Copanas, executive director at Generate Health, the backbone organization for FLOURISH. “We recognize that Black babies are at the greatest risk, so establishing this commitment to zero racial disparities enables us to pursue solutions based on their ability to close the infant mortality gap between Blacks and Whites.”

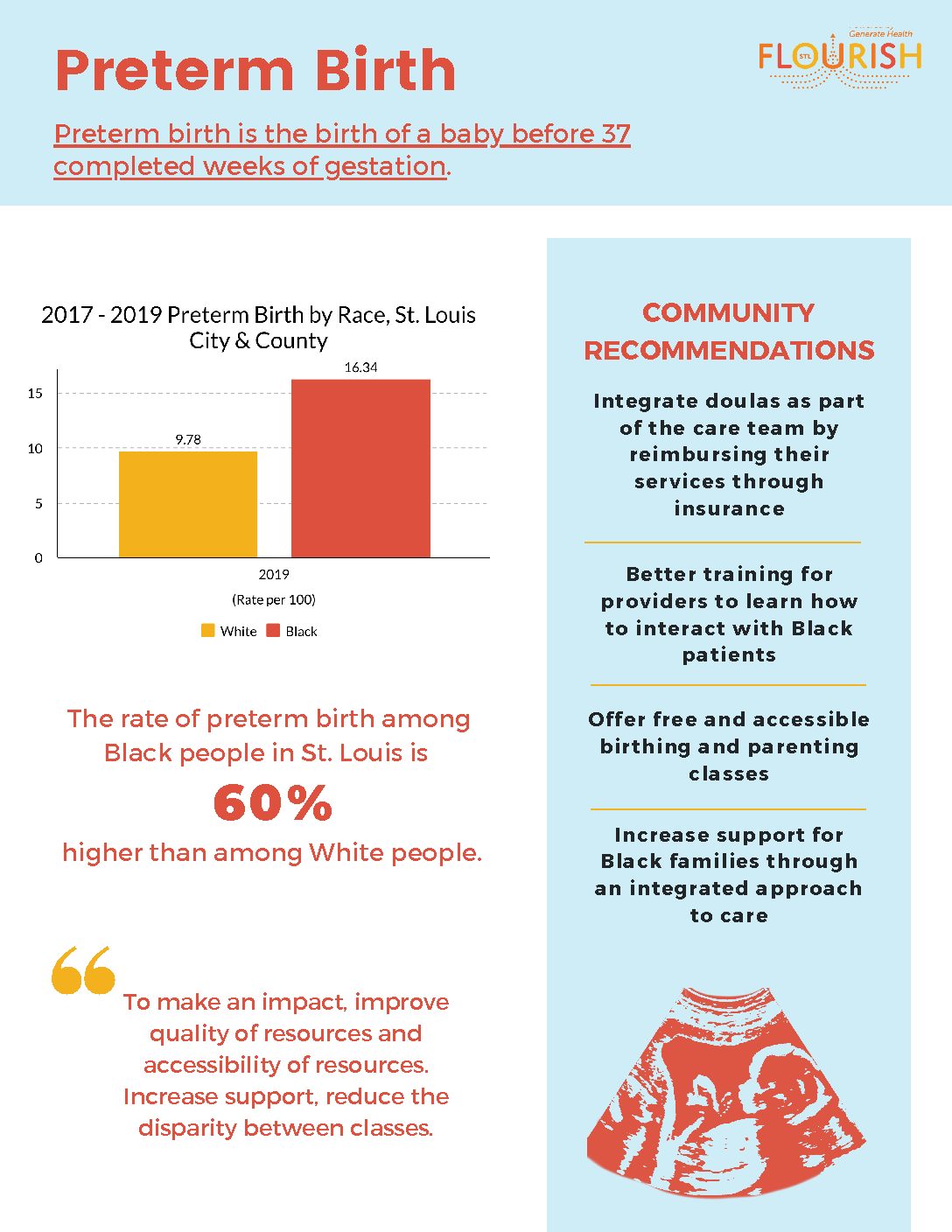

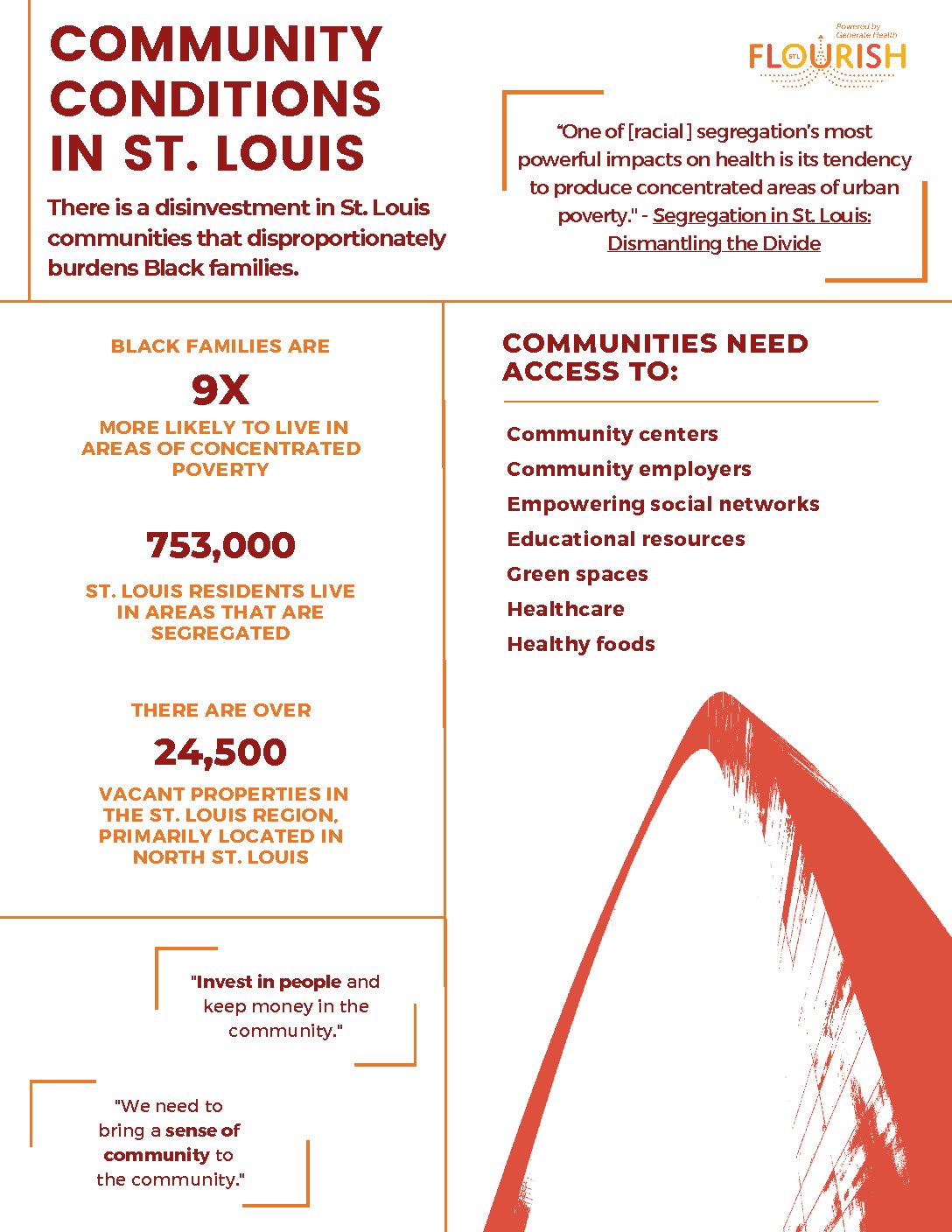

St. Louis is the sixth most segregated metro area in the U.S., which makes it a particularly difficult place to be born Black. And racial disparities exist across every indicator of opportunity to thrive in St. Louis.

- Black individuals in St. Louis have a 20-year difference in life expectancy compared to Whites.

- We are the fourth worst city for unequal unemployment – 21 percent of unemployed residents are Black, compared to just 6 percent who are White.

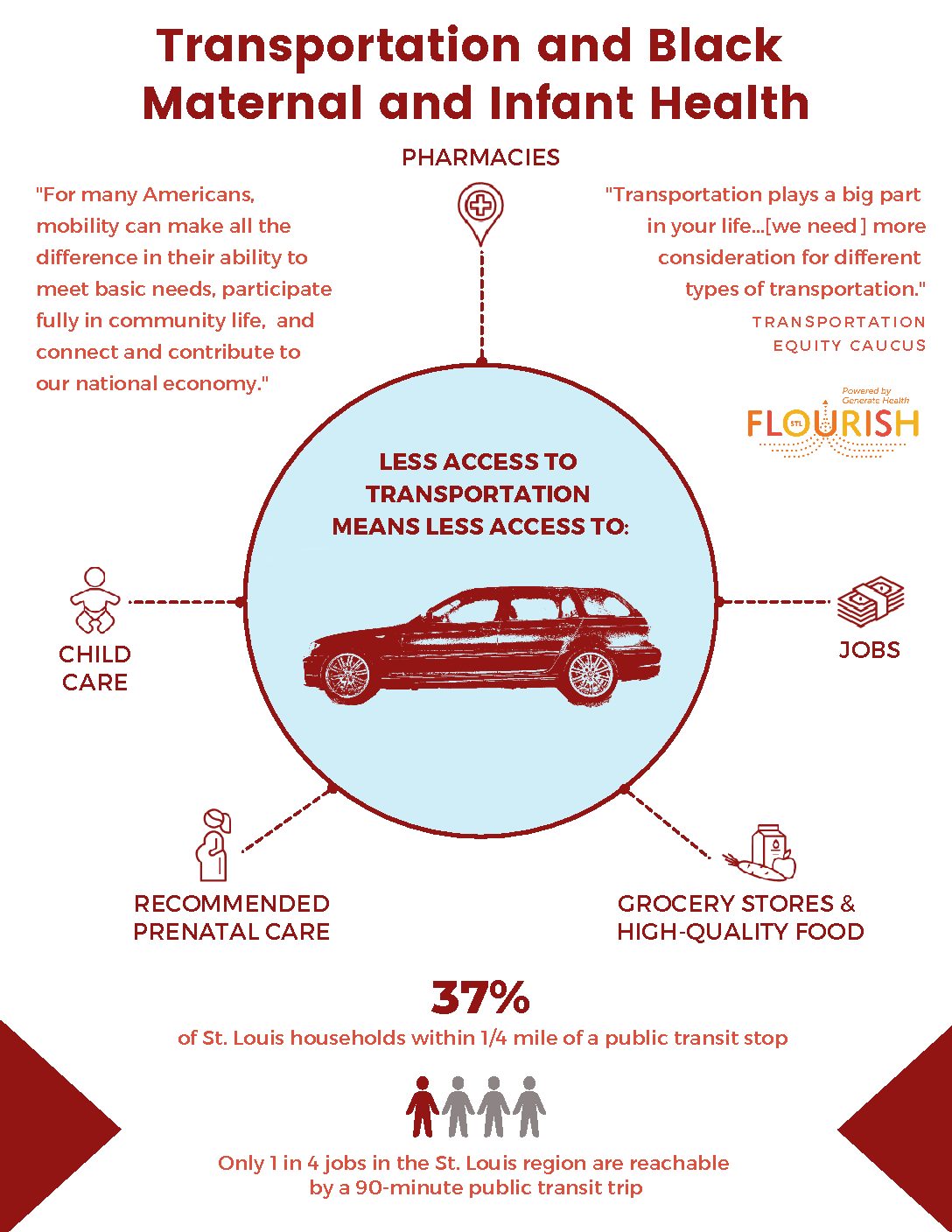

- Black families represent 80 percent of public transit riders, and only one in four jobs in the region are reachable by a 90-minute or less public transit trip.

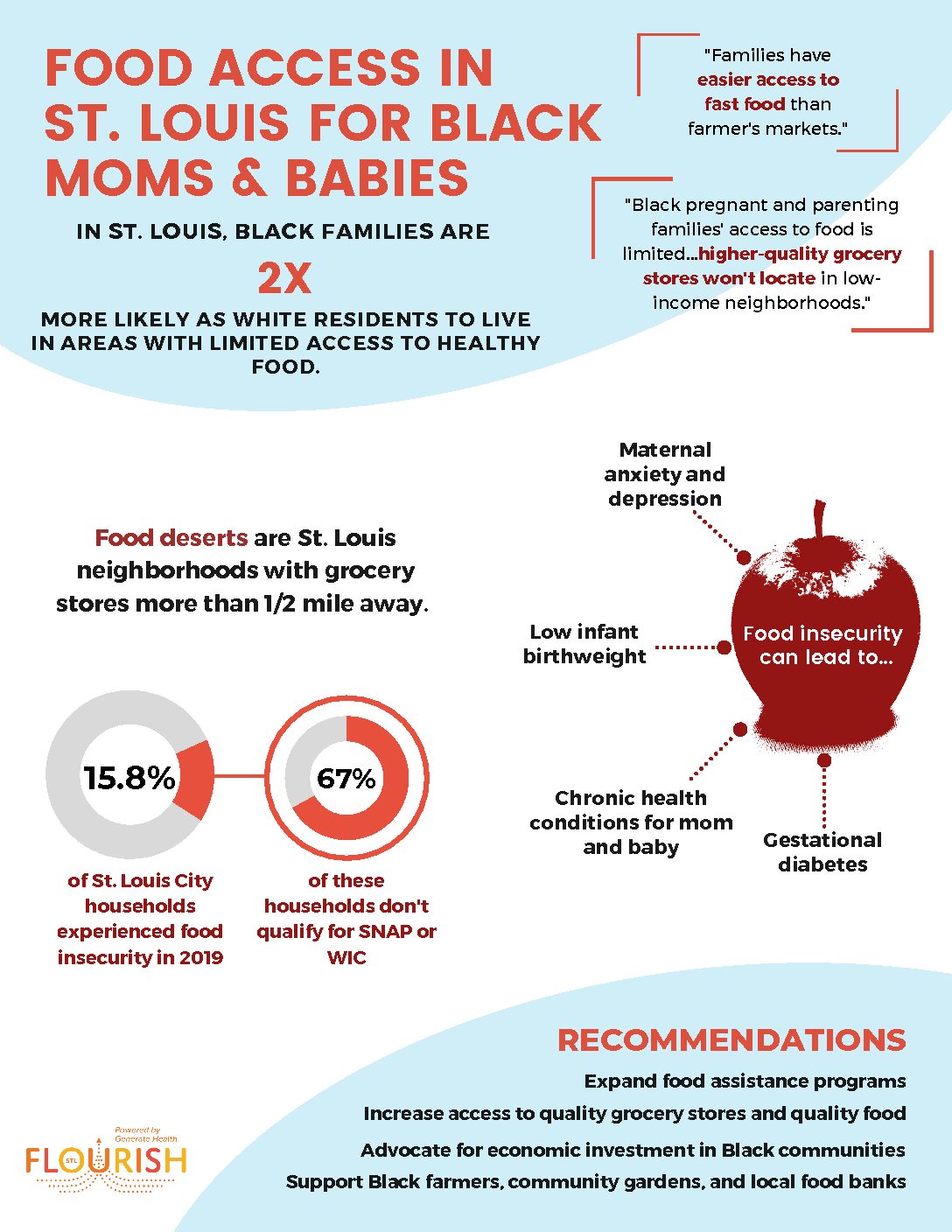

- One in four Black people are food insecure in the city of St. Louis.

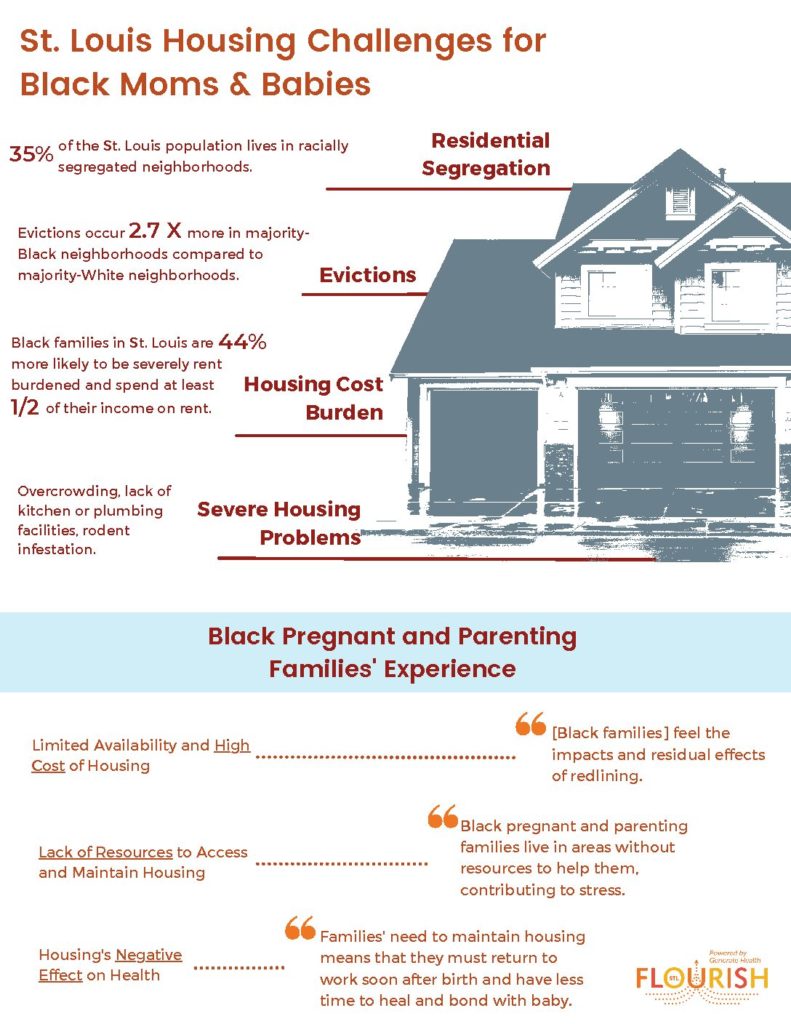

- One in four Black people have severe housing problems, including overcrowding, high housing costs, lack of kitchen or plumbing, and other challenging living conditions.

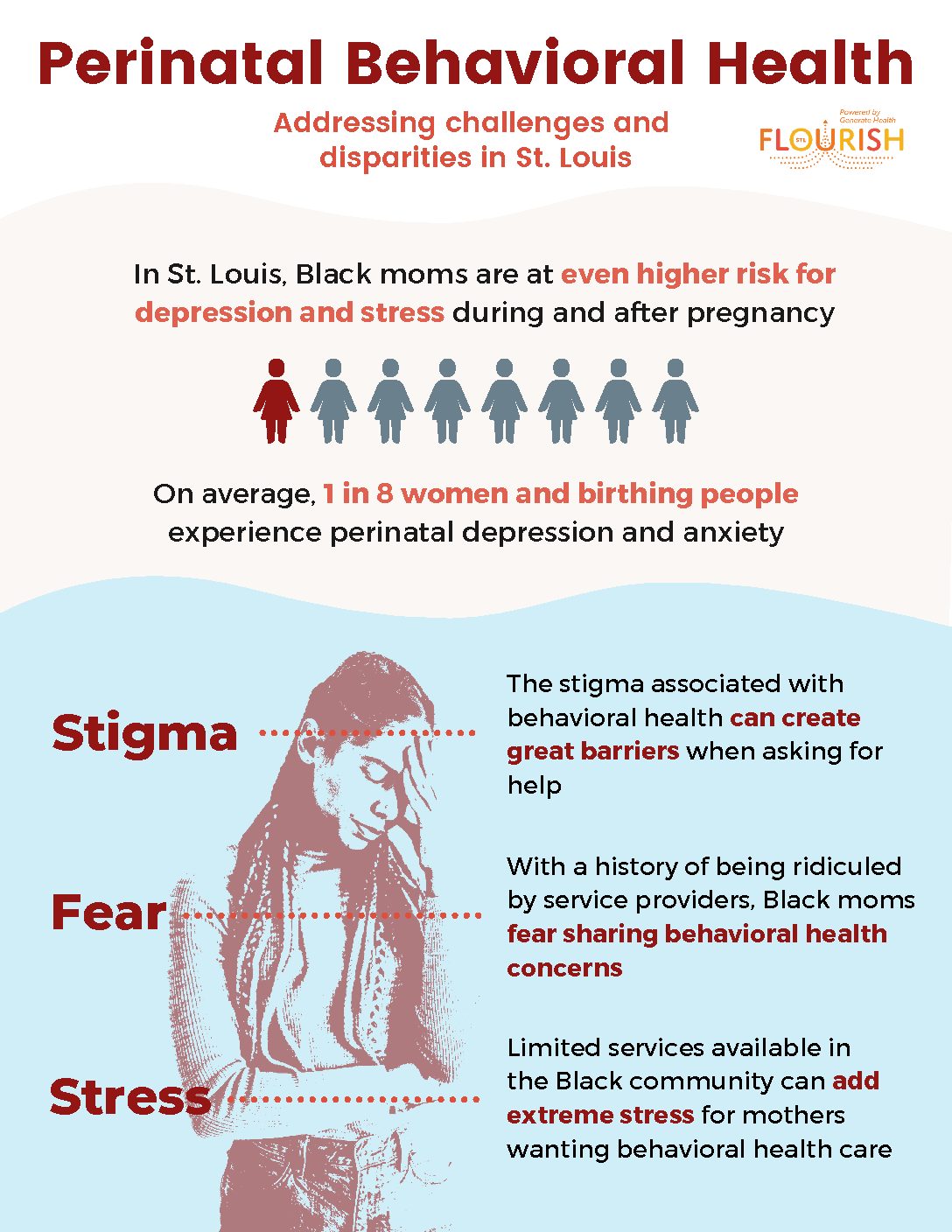

“The chronic stress families are facing from experiencing systemic racism and oppression everyday while navigating these barriers has a physical impact on their health, and the health of their children,” said Copanas. “Our role is to help change the ways institutions and systems are structured, so that Black babies and Black families experience equity in access to quality care and resources necessary to live a healthy life.”

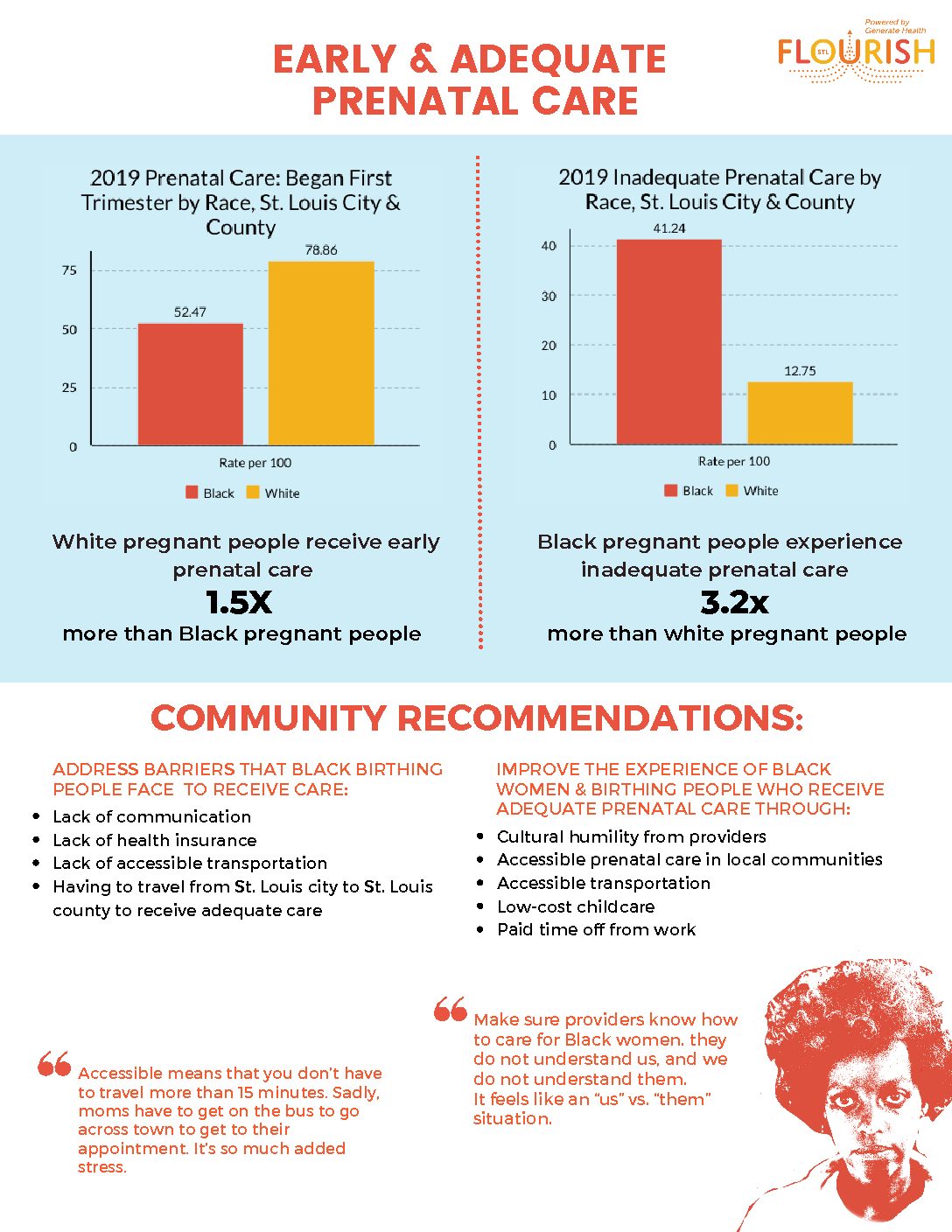

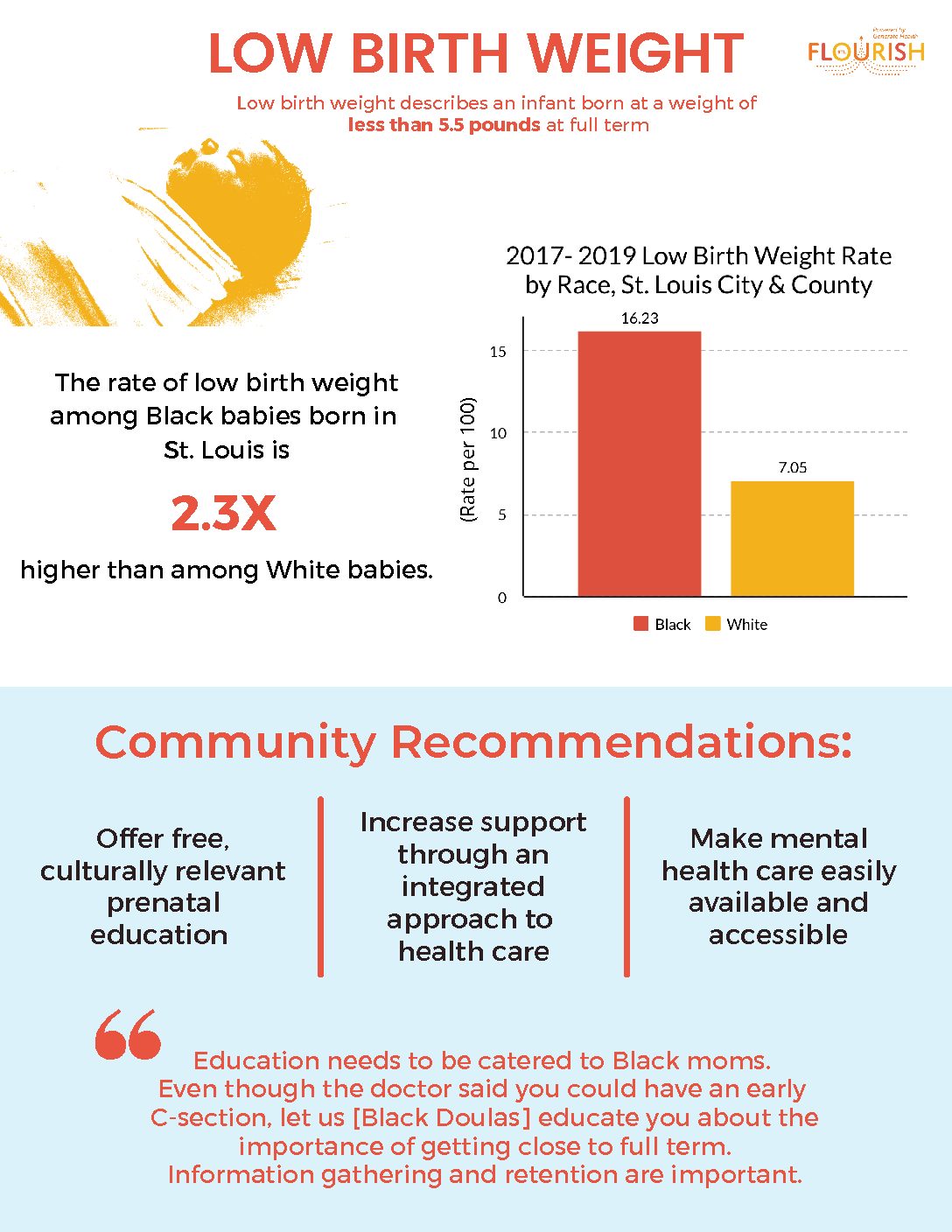

For example, more than one in three Black women in the city of St. Louis receive inadequate prenatal care because of community barriers. A mom may have to choose between working her hourly job and taking time off to go to the doctor, which puts her at risk for not being able to pay the utility bill this month. She may spend two hours on a bus each way to get to the doctor, and if the bus is late she could miss her appointment and have to wait weeks to get another.

Over the past several decades, the gap between the deaths of White babies and Black babies continued to grow across the U.S. – regardless of the mother’s socioeconomic status. Black women who are lawyers, doctors and engineers have higher rates of infant mortality than White women who didn’t finish college, according to the Harvard School of Public Health. And Black mothers are 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than White mothers, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

“Achieving zero racial disparities is a daunting undertaking, and will require people in our region to have honest conversations about racism in our area,” added Copanas. “But we believe it can be achieved – and must be achieved if we truly want to reduce infant mortality in our region.”