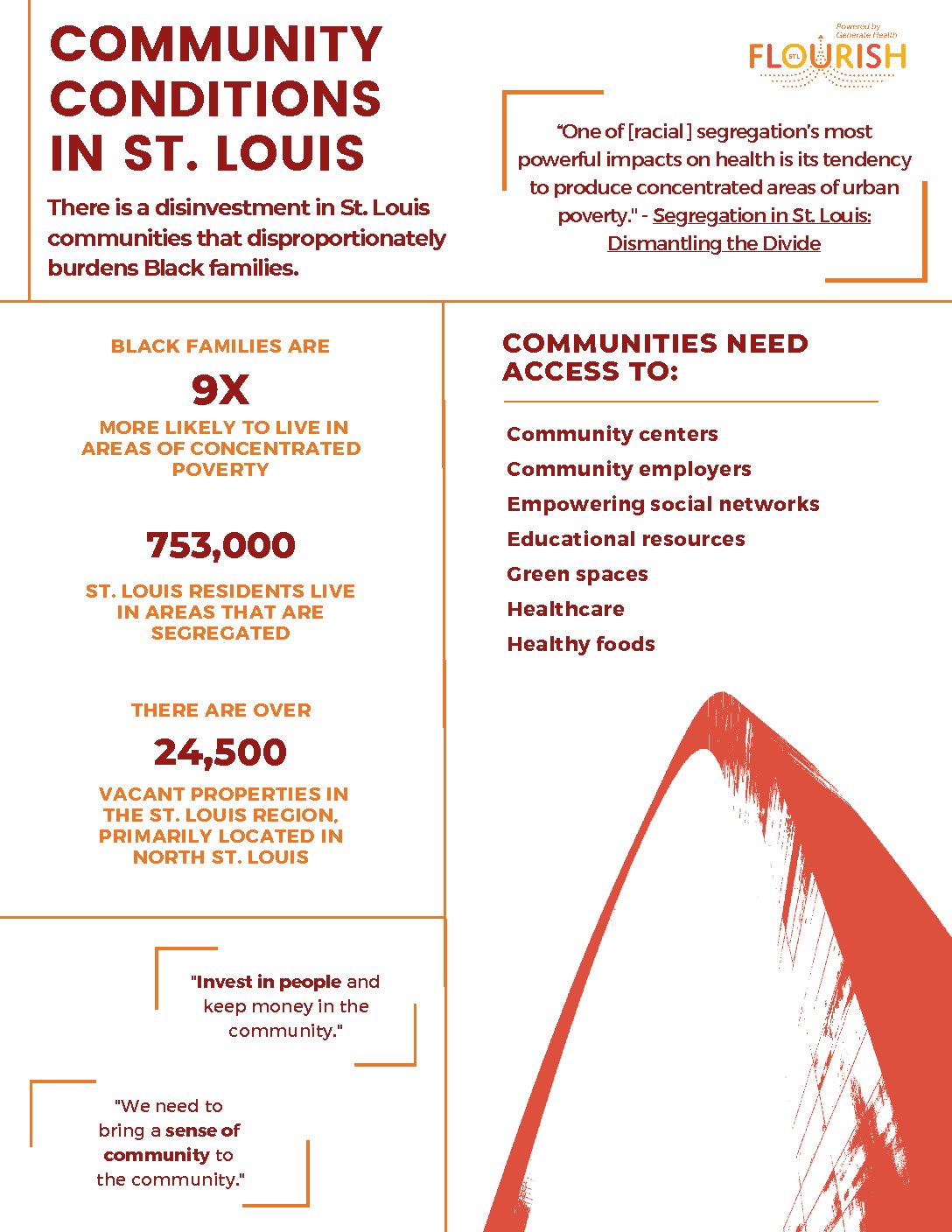

The data suggests, time and again, that our institutions and existing systems are not equal, and that this has racial repercussions. Black people in the region feel those repercussions when it comes to law enforcement, the justice system, housing, health, education, and income.

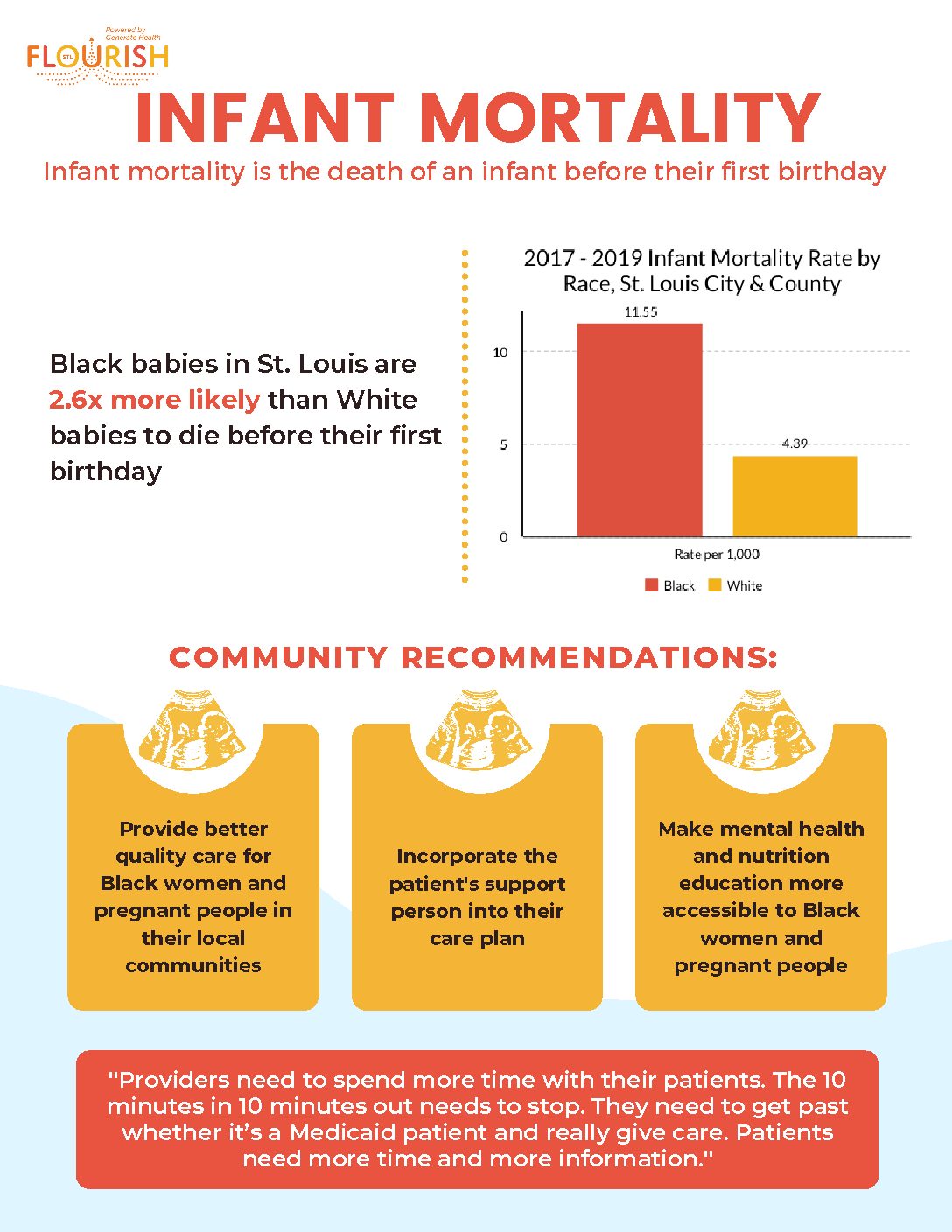

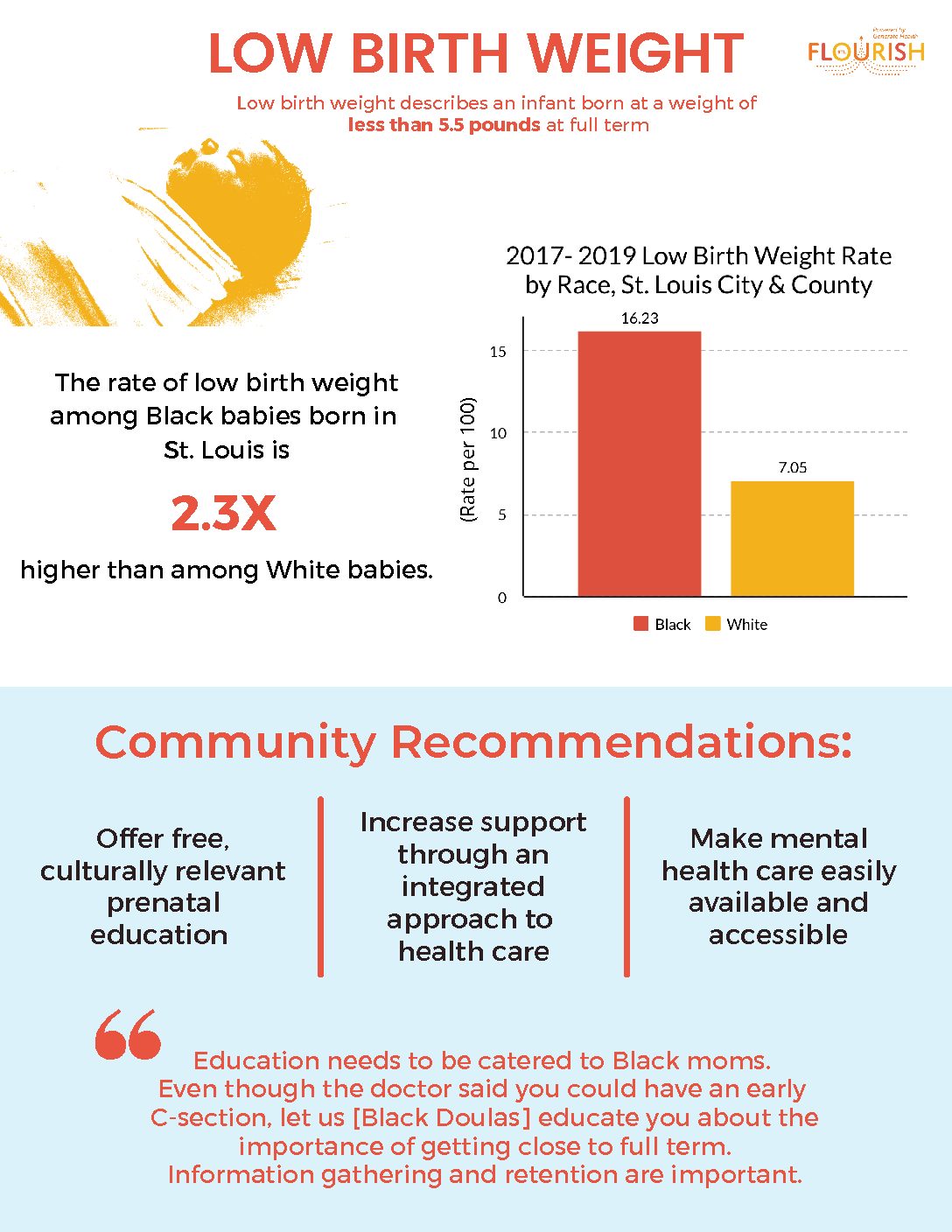

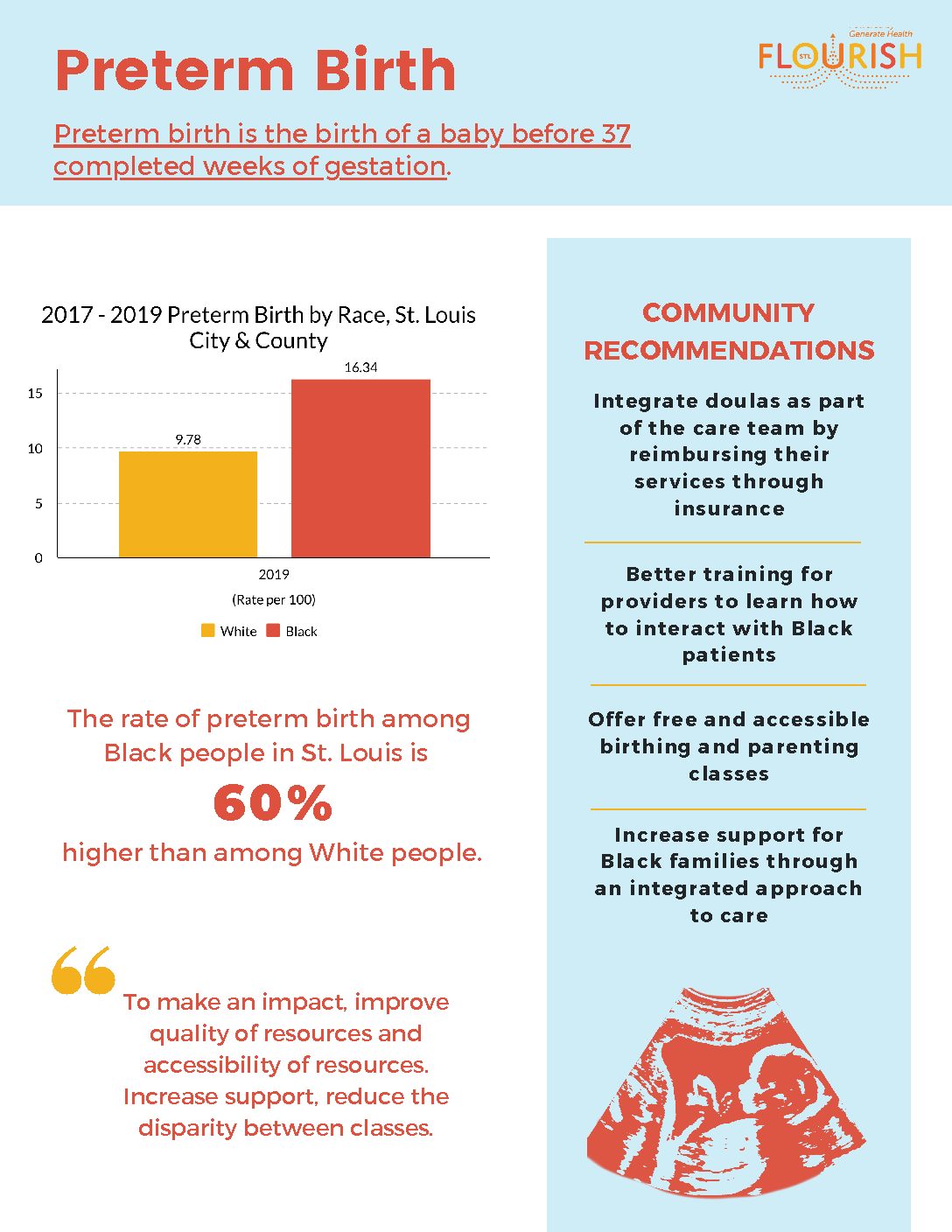

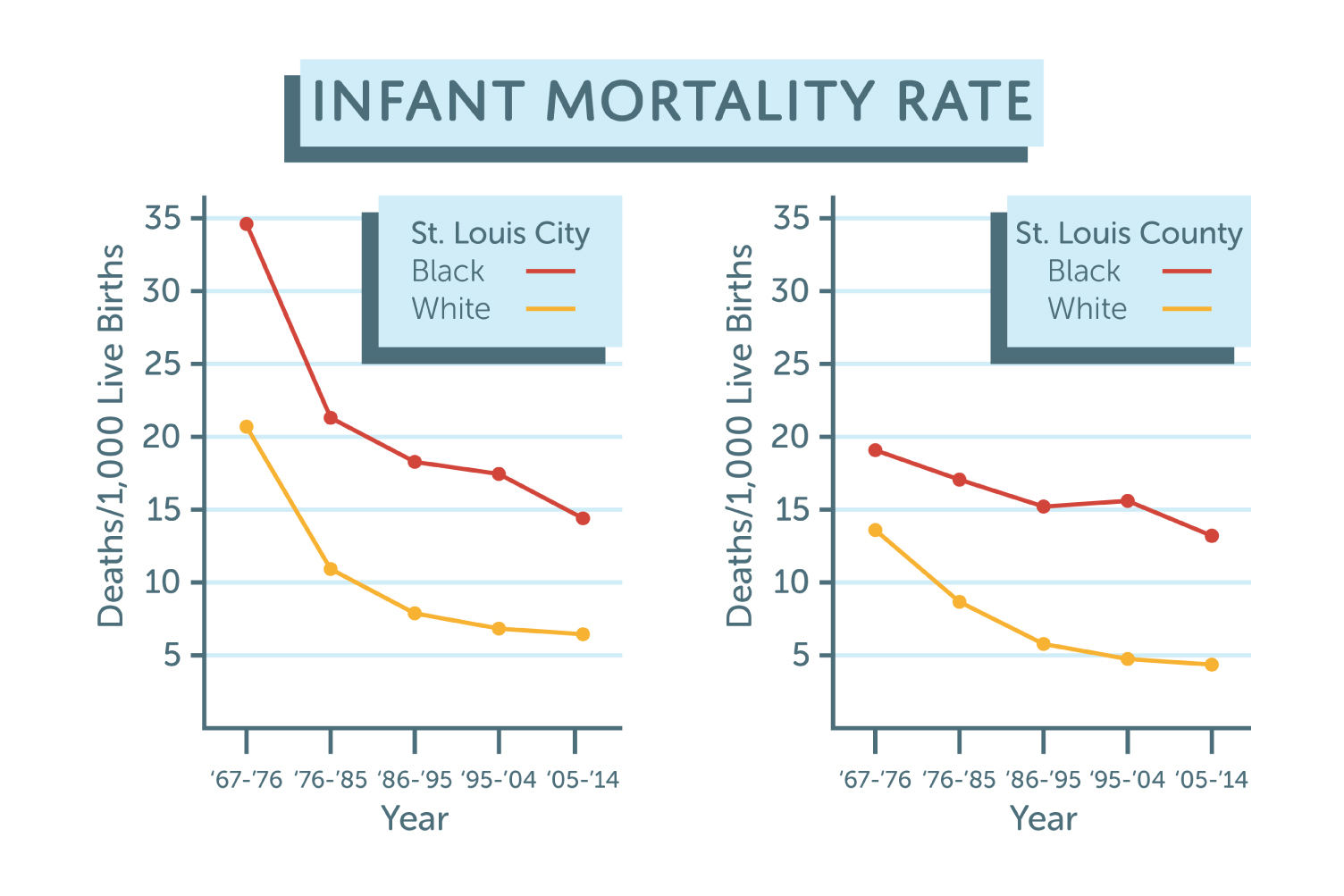

The racial disparity in health and in birth outcomes in our region is staggering. As a result, FLOURISH is keeping racial equity at the core of its approach to solving St. Louis’ infant mortality crisis.

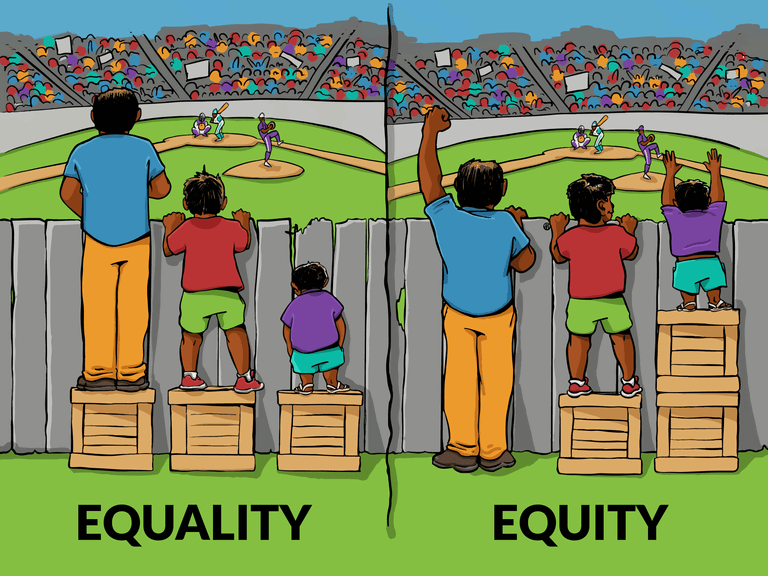

What do we mean when we talk about racial equity?

Racial equity is measured by outcomes. Racial equity means that all children have an equal chance of celebrating their first birthday. It means that every child in St. Louis, regardless of race or which zip code they occupy, will be able to grow into happy, healthy and successful adults.

If we want a region where race is no longer predictive of birth outcomes, we need to start by acknowledging that systems don’t work equally well for everyone.

Why are Black babies struggling to FLOURISH?

Centuries of racism have a direct impact on the health of Black families today. St. Louis is the sixth most segregated metro area in the U.S., which makes it a particularly difficult place to be born Black.

- Black people in St. Louis have an average life expectancy that is five years less than the life expectancy of white people.

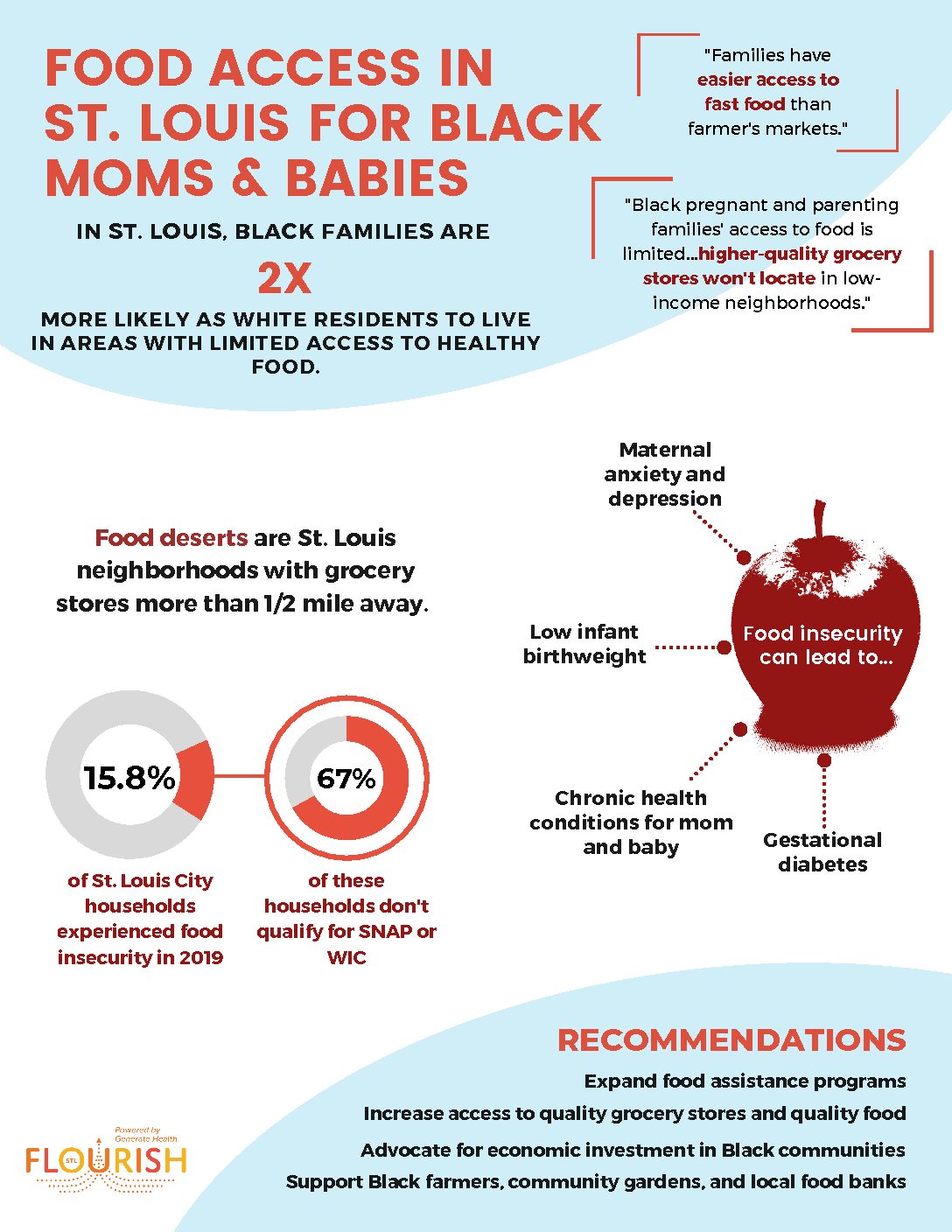

- Across St. Louis City and County, Black families are over seven times as likely as white families to receive food stamps. Black children face a serious challenge in accessing food when compared to white children across the region. Some live in food deserts, with no immediate access to a grocery store.

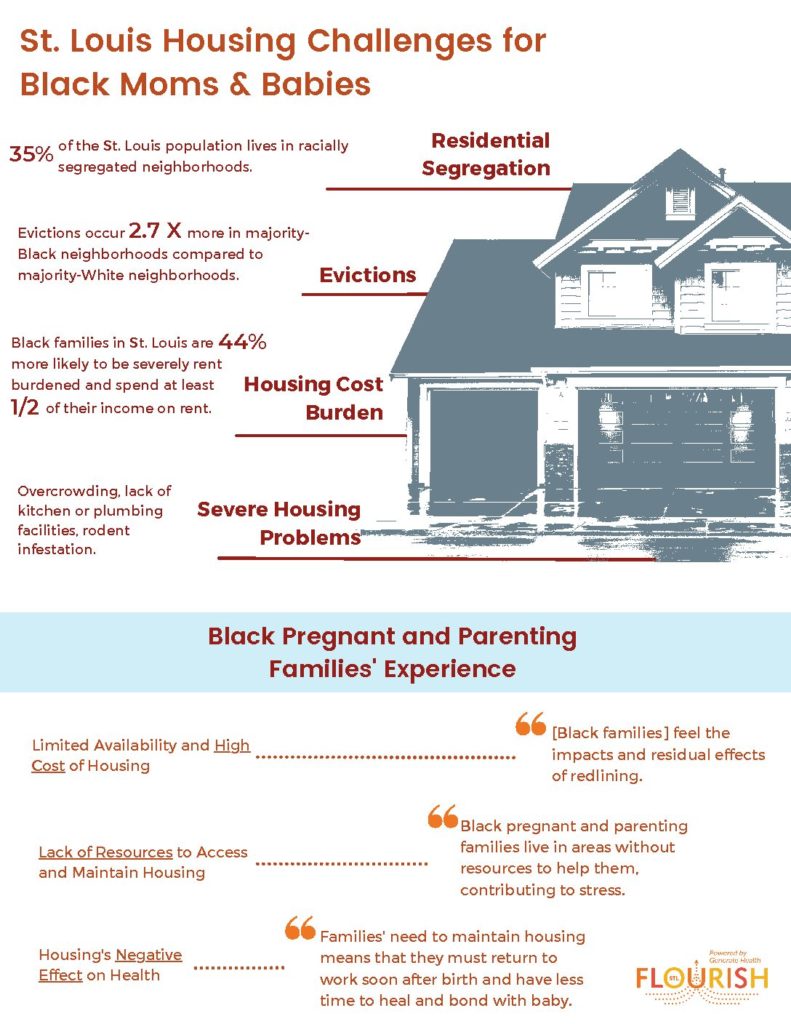

- About one in four Black people face severe rent burdens in St. Louis City and County, meaning they spend more than half of their income on rent.

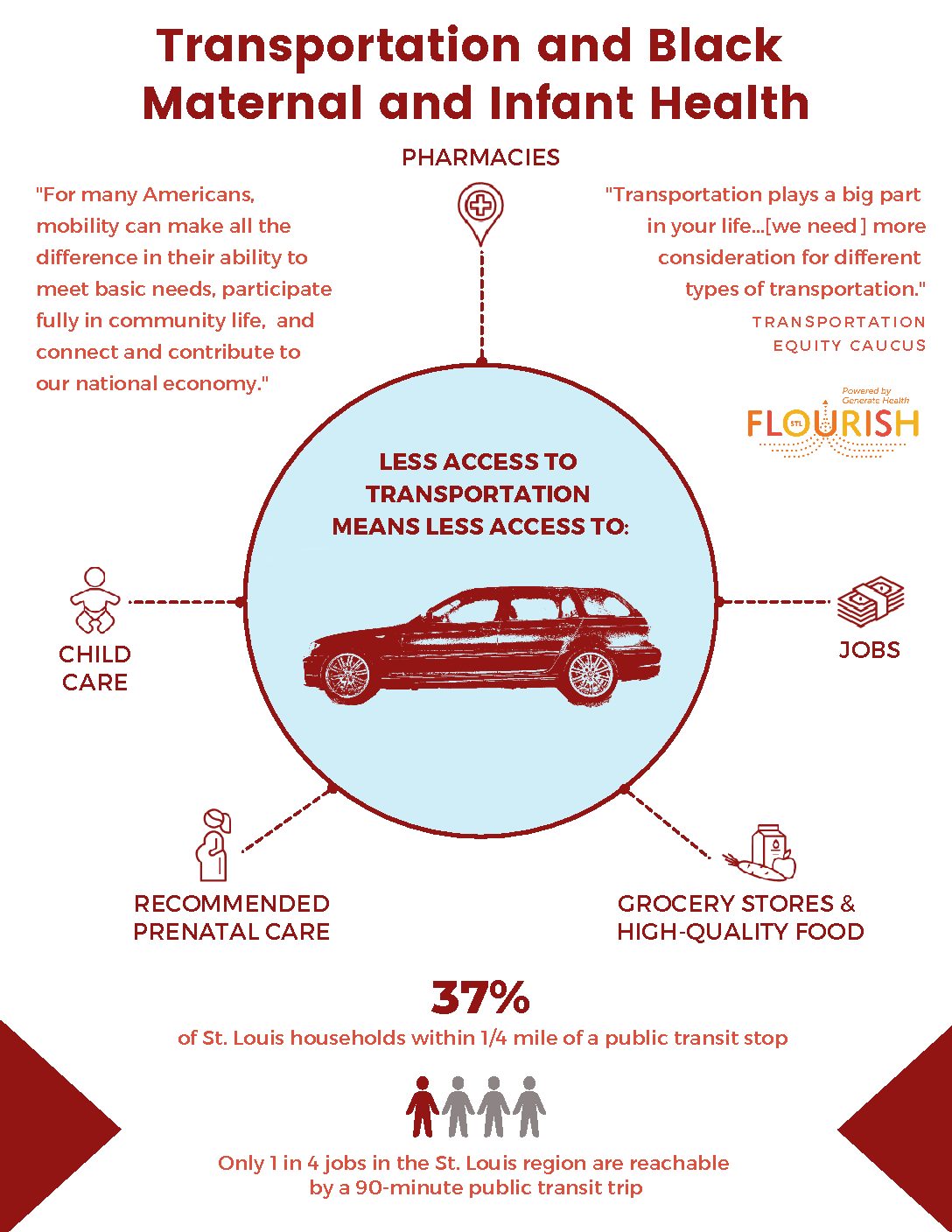

- Commuting time is considered one of the strongest factors in the odds of escaping poverty. In both St. Louis City and County, Black residents face longer commutes. In St. Louis County, Black residents’ commutes are about 28% longer, and in the City of St. Louis, they are about 22% longer.

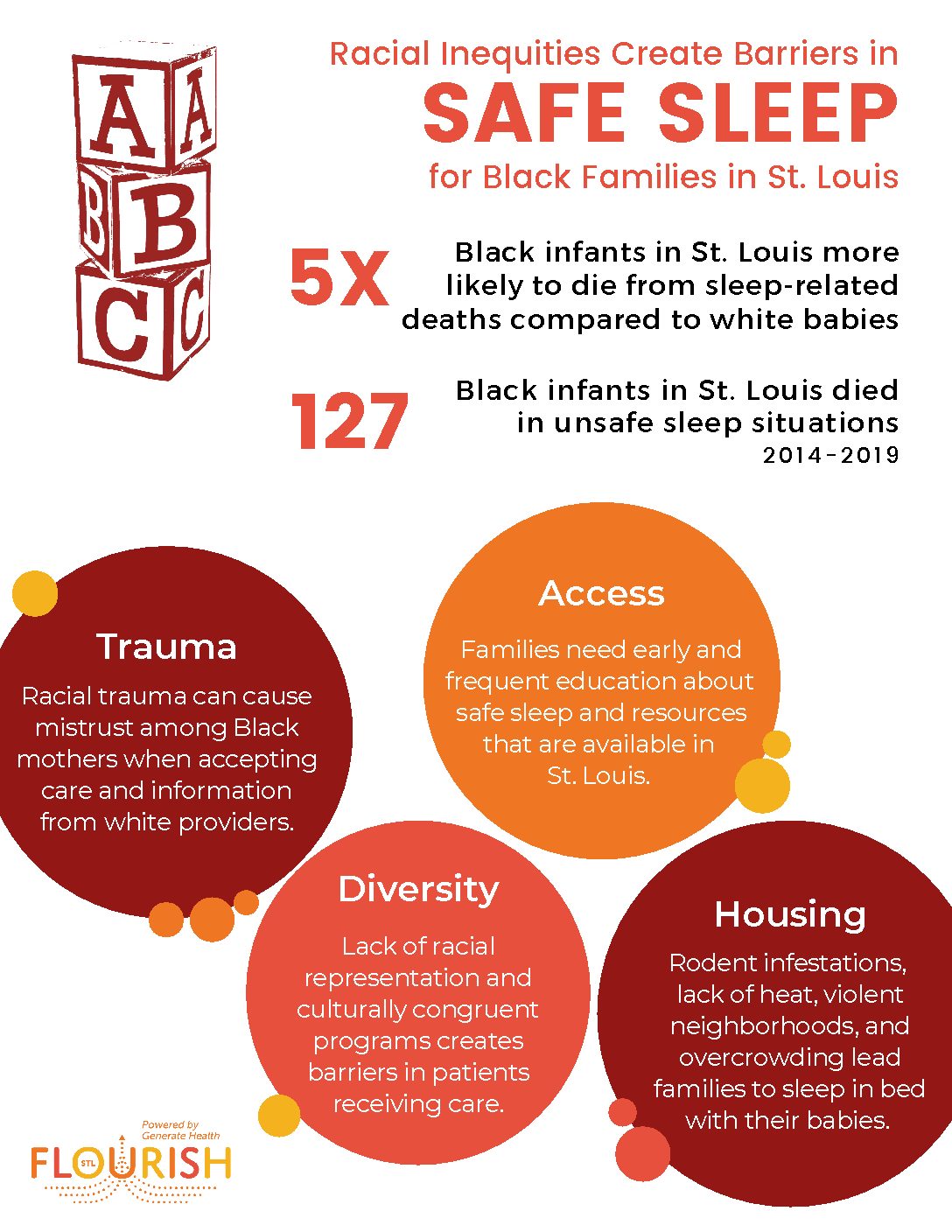

- Black babies in St. Louis City and County are seven times more likely to die from a sleep-related death than white infants.

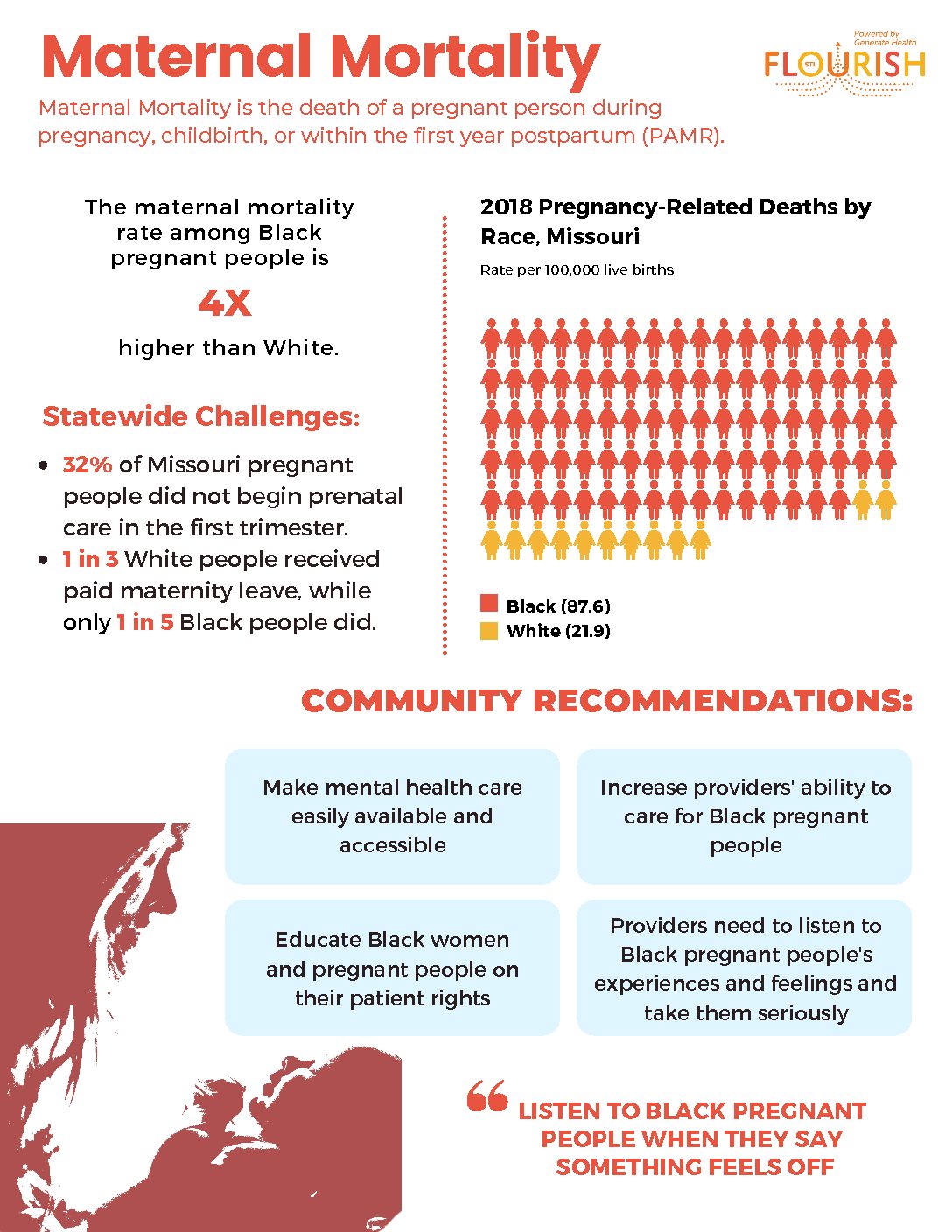

Over the past several decades, the gap between the deaths of White babies and Black babies continued to grow – regardless of the mother’s socioeconomic status. Black women who are lawyers, doctors and engineers have higher rates of infant mortality than white women who didn’t finish college, according to the Harvard School of Public Health. And Black women are 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than White women, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

That’s why FLOURISH is committed to improving systems in St. Louis, so we have zero racial disparities in infant mortality by 2033.

Graph of Birth Outcomes by Race, courtesy of Forward Through Ferguson

Image Credit: Interaction Institute for Social Change, Artist: Angus Maguire

Infant Health in Greater St. Louis

Download a report from the Missouri Foundation for Health to learn more about racial equity and infant mortality.