Recently, Kendra Copanas, Executive Director of Generate Health, which organizes and coordinates the FLOURISH St. Louis initiative, sat down for a Q&A session to highlight some of the ways FLOURISH St. Louis is taking a different approach to solving St. Louis’ infant mortality crisis. Her responses shine light on why it’s been difficult for St. Louis to make a significant reduction in its infant deaths.

Q: How is FLOURISH St. Louis’ approach different from what’s been done in the past to reduce infant mortality in St. Louis?

A: Historically, we have looked to advances in health care delivery and public health for solutions to improving infant mortality. Now, we’re looking at the issue from more than just a medical or health care perspective. We’re looking for solutions outside of health care.

It is now understood that factors related to the environment account for 70 percent of premature deaths and genetics only 30 percent. Within that 70 percent, medical care only makes up 10 percent – the rest, the majority is shaped by individual behaviors, social factors and environmental exposures. Behaviors happen within a social context and are influenced heavily by the environment.

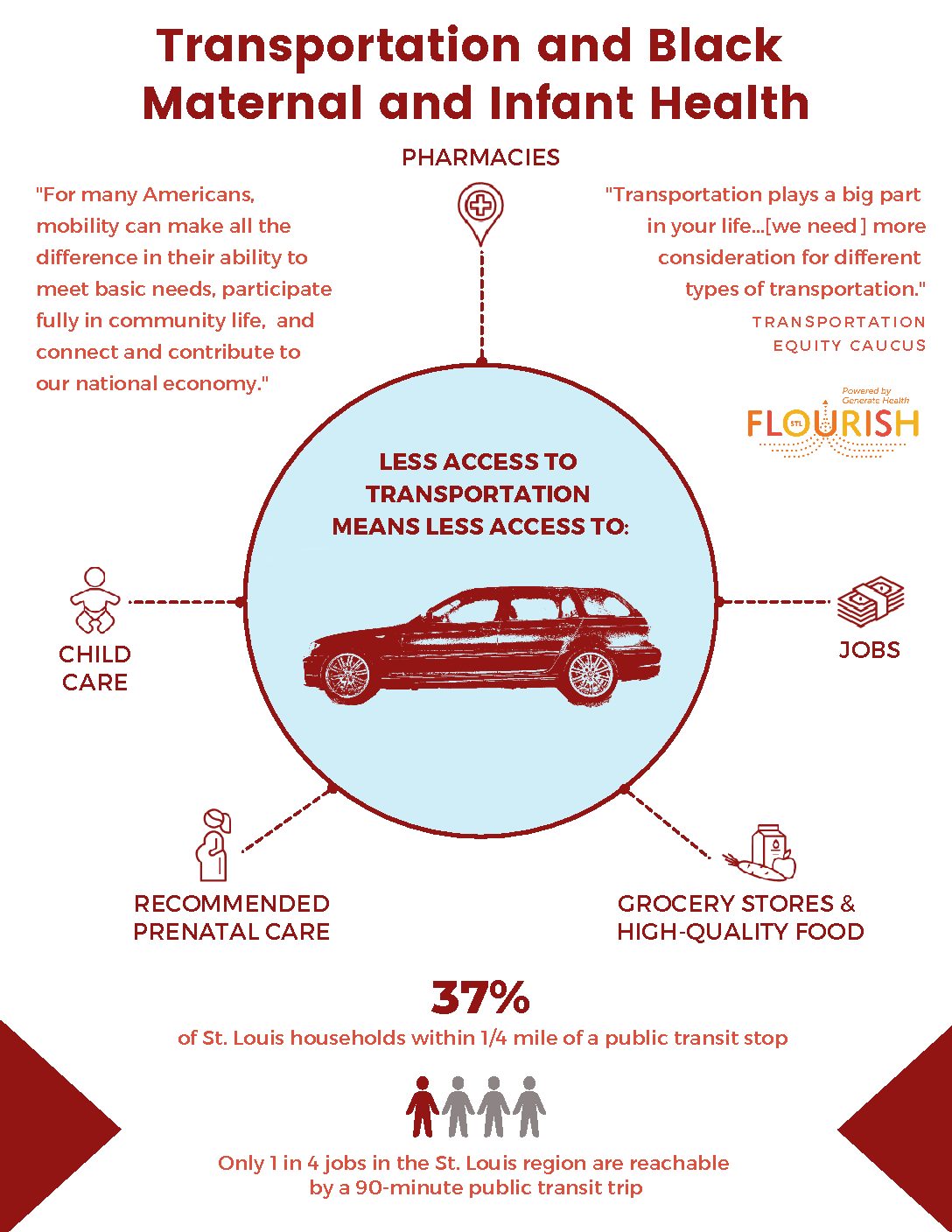

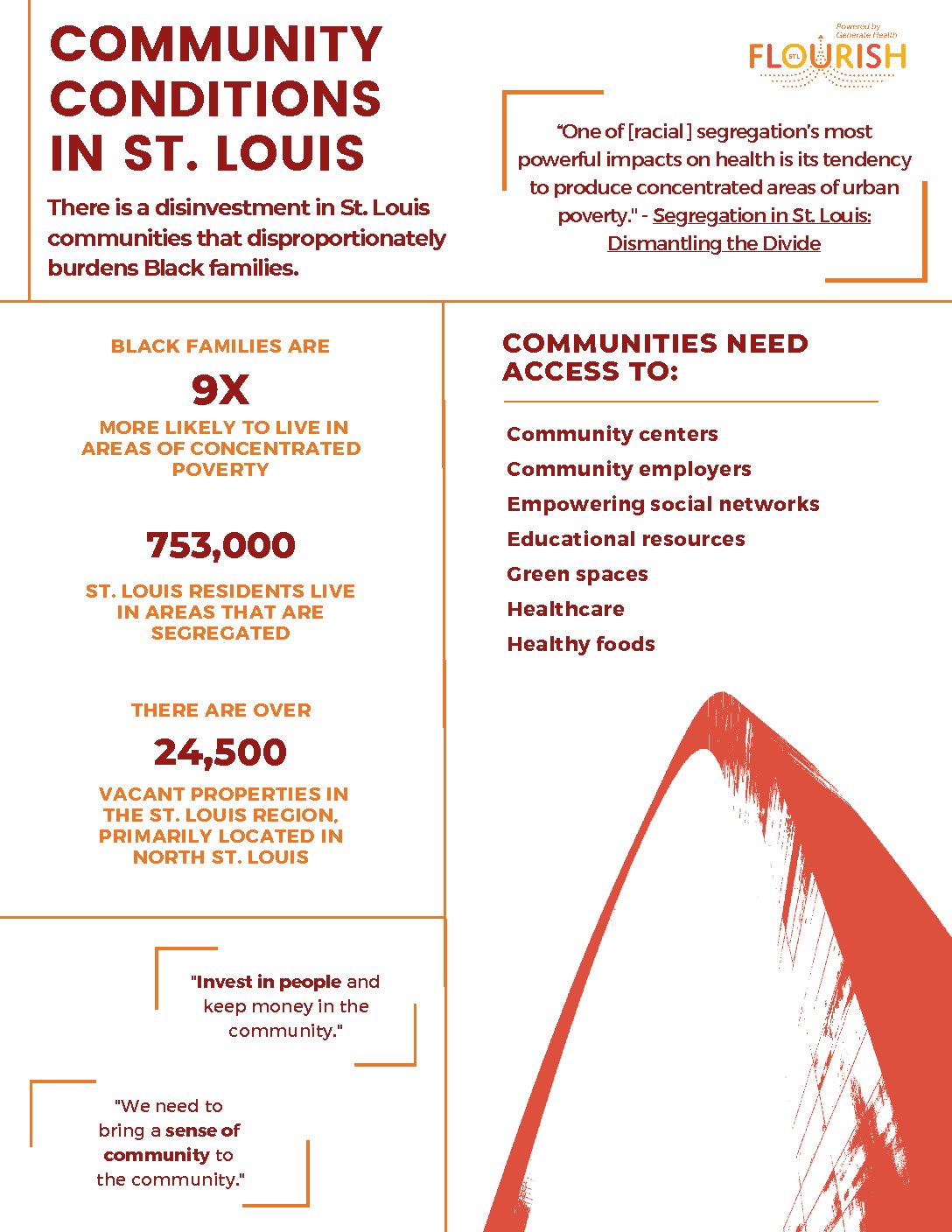

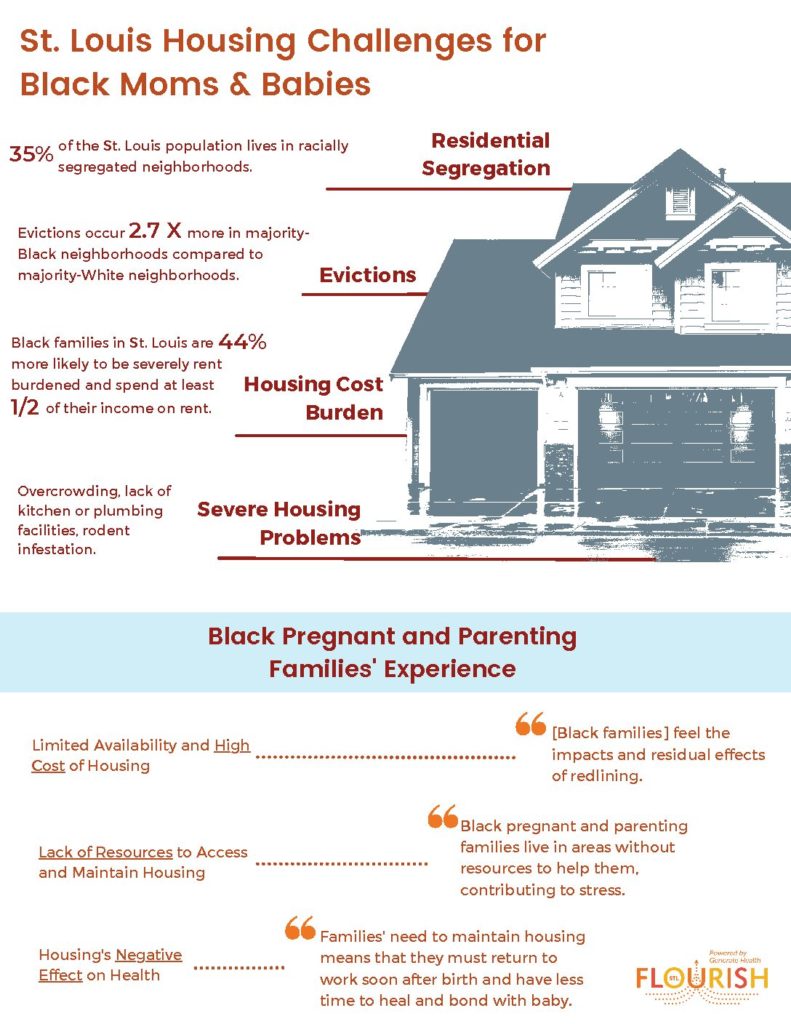

The causes of infant mortality are complex. So, it will take all different parts of our community to be involved – more sectors than we’ve ever attempted before – to address this complex and multifaceted issue. We’re engaging stakeholders who haven’t seen themselves as a part of this solution, but who actually have a critical role to play in reducing infant mortality, including the transportation, housing and business communities.

FLOURISH St. Louis has brought together a Cabinet of education, faith, business, health care and mental health leaders, as well as impacted parents. Together, they looked at our local data and reviewed what other cities have done to help their moms and babies. They also conducted listening sessions with 126 family members to understand the stories behind the data and the needs of the community.

The Cabinet is now in the process of developing recommendations on which actions will most help the region reduce infant deaths. To effect the level of change needed, we must focus collaboratively on policy and systems changes rather than individual programs.

Q: Why is a different approach needed?

A: Over the years, St. Louis has made improvements in infant health, but it’s been incremental. In order to see a significant reduction in infant deaths, we need to try new things. In the past, we have relied on medical solutions to address the issue. But research now shows that there is more complexity in the factors that impact infant mortality, so we need to bring new solutions to the table.

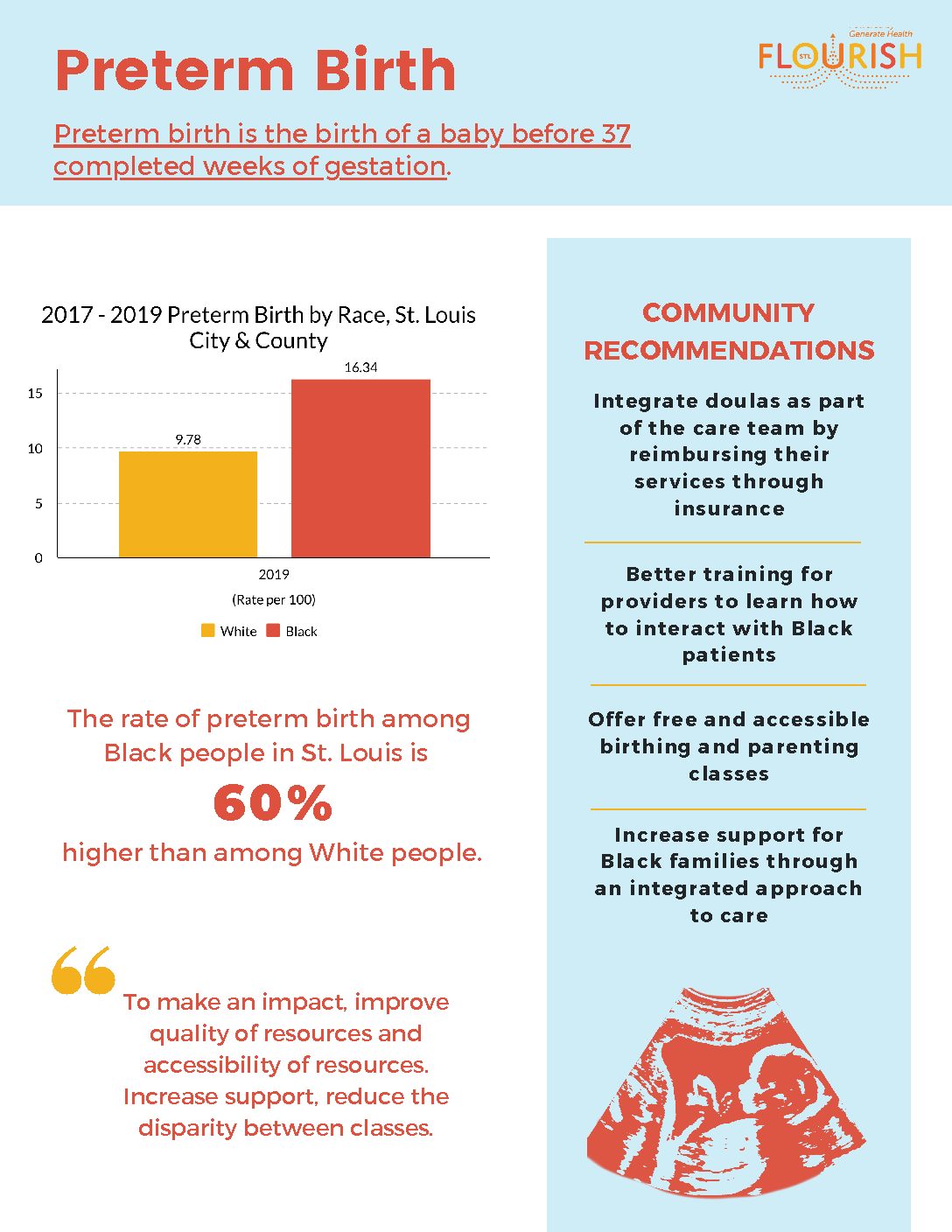

For example, stress is one of the triggers of premature birth, which is the leading cause of infant deaths in our region. But, you can’t use medical technology or just give medications to reduce stress. You need to change the conditions in the community that trigger stress – things like racism, lack of opportunities for living-wage jobs and transportation barriers. These are outside of the realm of medicine.

Q: Why has it been so hard for St. Louis to take this approach in the past?

A: This approach takes the long view; it does not provide immediate results. What it does provide is big results – substantial and sustainable results that can make a permanent shift in the health of moms and babies. Long-term sustained efforts extend beyond election cycles, grant cycles and yearly earnings reports. Typically, funding to address infant health has focused on creating new programs, not at looking across the community for big policy and system changes. St. Louis has excellent direct service programs, but they are not enough on their own. Programs can only impact the people they can reach, and there are issues within our systems that keep people from accessing the services we already have available in St. Louis. People aren’t able to reap the benefits of those services equitably. That’s something we must address in order to see big change happen.

This approach is hard for St. Louis because it requires addressing multiple systems, such as transportation, education and housing that are interrelated and difficult to change. The set of decisions that organizations, regional planners and funders make about the allocation of resources significantly impacts individuals’ lives at the systems level. And many don’t realize the impact it has. That’s why we need to come together as a community to learn more about these impacts.

Q: How will the results from this approach be different from what has happened in the past?

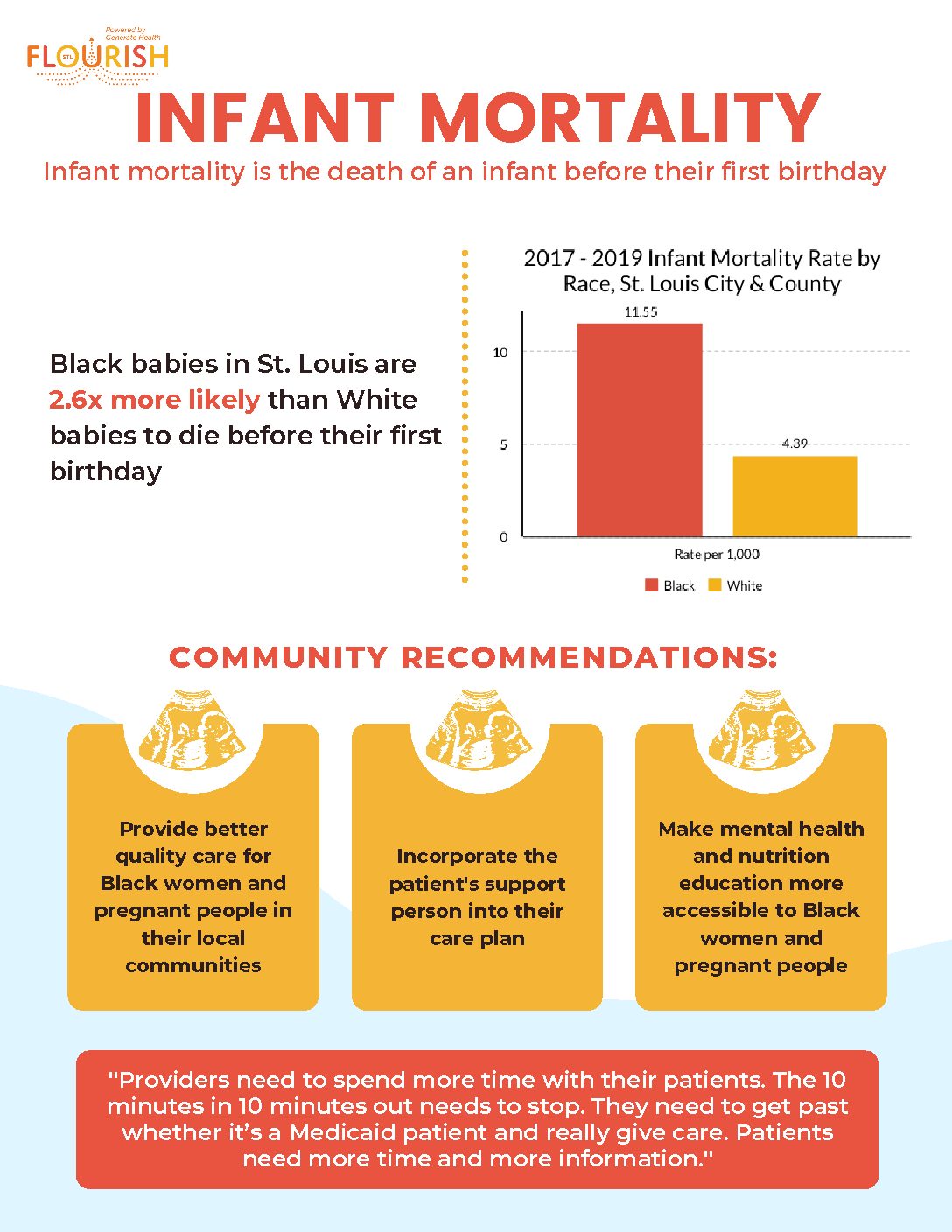

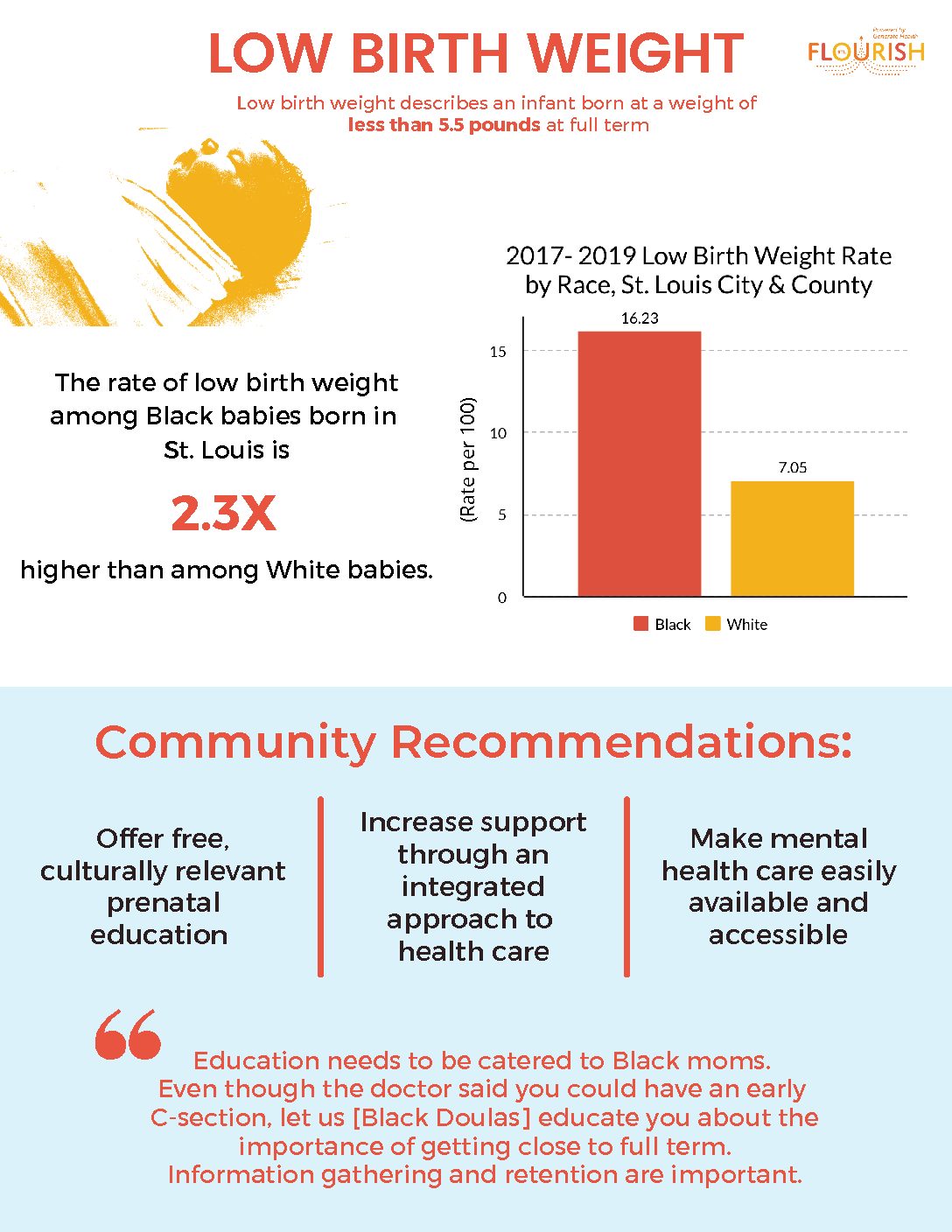

A: We’ve seen some reduction in infant deaths in St. Louis. They’ve primarily come from keeping more premature babies alive thanks to the advancement of medical care and technologies. What we haven’t seen is a significant reduction in the number of babies who are born too early or too small to begin with.

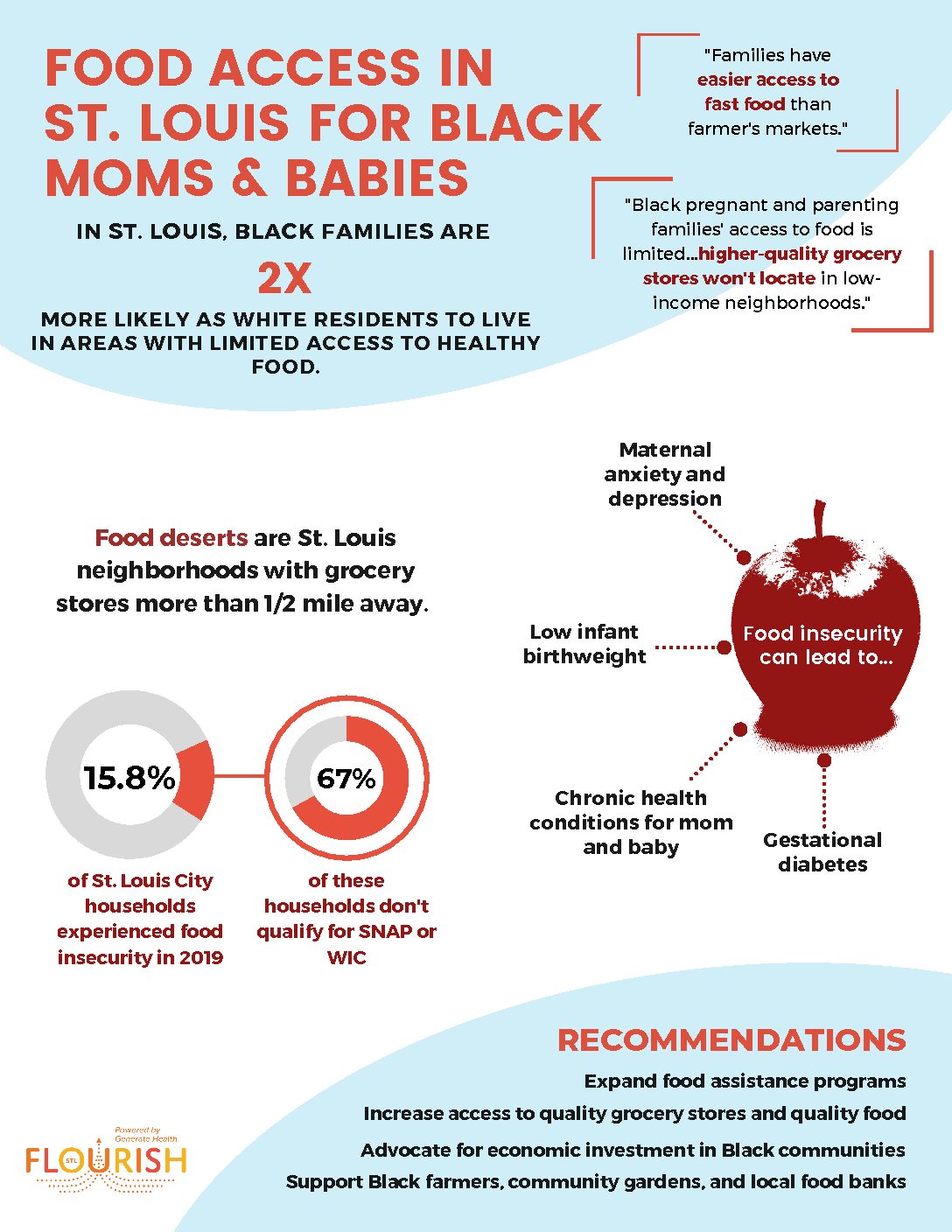

How we reduce the number of babies born too early or too small is by addressing the environment, systems, conditions and polices that help or hinder women’s access to the things they need to support their health in addition to providing access to traditional medical care. That’s what this new approach does – it is a community-based, multi-sector approach that is looking long term and addressing a multitude of interrelated systems. Rather than creating new programs, this is about improving conditions in the community. It’s a broader scale effort and based on a shared agenda with cross sector input. The responsibility is owned by the community. Therefore, the results are more sustainable.

Q: You talk about how reducing infant mortality will require making systemic change. Can you describe what that means?

A: Systemic change means changing the very conditions and environment in which you live. Giving equitable access to care and services available – equal access to foods, education, living-wage jobs. Everyone should have the same chance to utilize the services available, but they don’t.

It also refers to how all parts of our community need to work together more seamlessly. For example, we have multiple jurisdictions in St. Louis that must work together in order to get things done. To make this work, they need to be aligned and have similar goals. That’s part of what FLOURISH St. Louis is aiming to do – align our entire region around strategic priorities that will have the greatest impact on reducing infant deaths.

We are bringing the community together to create systemic change, the impact of which can extend beyond what a single program can achieve. We’re aiming to create a significant and lasting impact for multiple programs, agencies and the entire community.

Q: What are examples of systemic change that you’ve seen in St. Louis or other regions?

A: One St. Louis example is that we’ve seen advances across our region with the development of bike paths. Great River Greenways, Trailnet and multiple municipalities worked together to transform areas that crossed multiple municipalities into connected healthy bike paths.

We’ve also seen large policy change around smoking when both the City and County came together to ban indoor smoking in most public buildings. That was a systemic change to promote public health.

Also, when our safety net health care system was threatened with the loss of funding, the St. Louis Regional Health Commission, City and County health departments, community health centers, and area hospitals came together to improve access to care by coordinating funding across the safety net system.

FLOURISH St. Louis believes that significant change can be achieved if we come together as a community in new ways to make our region a place where babies thrive and families flourish. We value the role and perspective that a variety of sectors can play in making this change happen, and encourage the community to find out how they can get involved.